Historic Emancipation Celebrations Across the State

On January 1, 1863, in the third year of the US Civil War, Republican President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared all enslaved people within the rebellious states “are, and henceforward shall be free.” In Union Army-occupied areas of Florida, such as Key West and St. Augustine, local populations felt the effect of the Proclamation immediately. The newly freed people planned joyous events to celebrate the end of their bondage. However, freedom did not arrive for enslaved people in the rest of the state until over two years later, when the Confederate Army formally surrendered Florida to the Union troops.

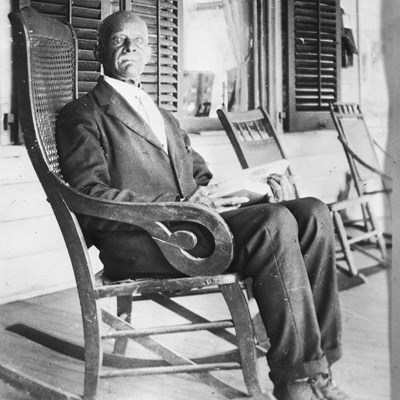

Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, marked the beginning of the war’s conclusion. On May 10, 1865, Union Brigadier General Edward Moody McCook and his men arrived in Tallahassee to assume control of the city. Ten days later, on May 20, Moody’s men announced the Emancipation Proclamation to be in effect throughout the area. Enslaved people celebrated their emancipation with parades, speeches, and other festivities. Freedmen and their descendants continued to celebrate May 20 as Emancipation Day over the decades that followed and into the present. Similarly, the celebration of Juneteenth commemorates June 19, 1865, when the Union Army arrived in Galveston, Texas, one of the last Confederate-held areas. Their arrival brought news of freedom to 250,000 people still enslaved in Texas.

Historically, some Florida communities celebrated in January to coincide with the first issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation. Others celebrated in May to mark the Proclamation’s statewide enforcement. Sometimes communities even celebrated both dates within the same year, as Tallahasseeans often did in the 1870s and 1880s.

Many commonalities link Emancipation Day celebrations across the state and throughout time. Black benevolent and mutual aid societies organized some of the earliest celebrations, including the Freedmen’s Benevolent Society in Tallahassee and the Freedman’s Aid Society in Jacksonville. The slate of events usually included parades, music, and speeches by political or religious leaders. Finally, no celebration was complete without food. The food and funds supplied by community members supported everything from lakeside picnics to grand banquets. As the years passed, Black communities across the state have preserved and continued these important remembrances and celebrations.